06 November 2010

Rob Ford, Wayne Roberts, Hans Blumenfeld & Toronto's Mayoral Election

In the late 1970s I was a graduate student living in Alexandra Park Housing Co-operative near Queen and Bathurst. Wayne Roberts was also living there. He had just finished his PhD.

28 October 2010

Toronto’s 2010 Mayoral Election: A product of deep seated resentment about economic realities and trends?

15 October 2010

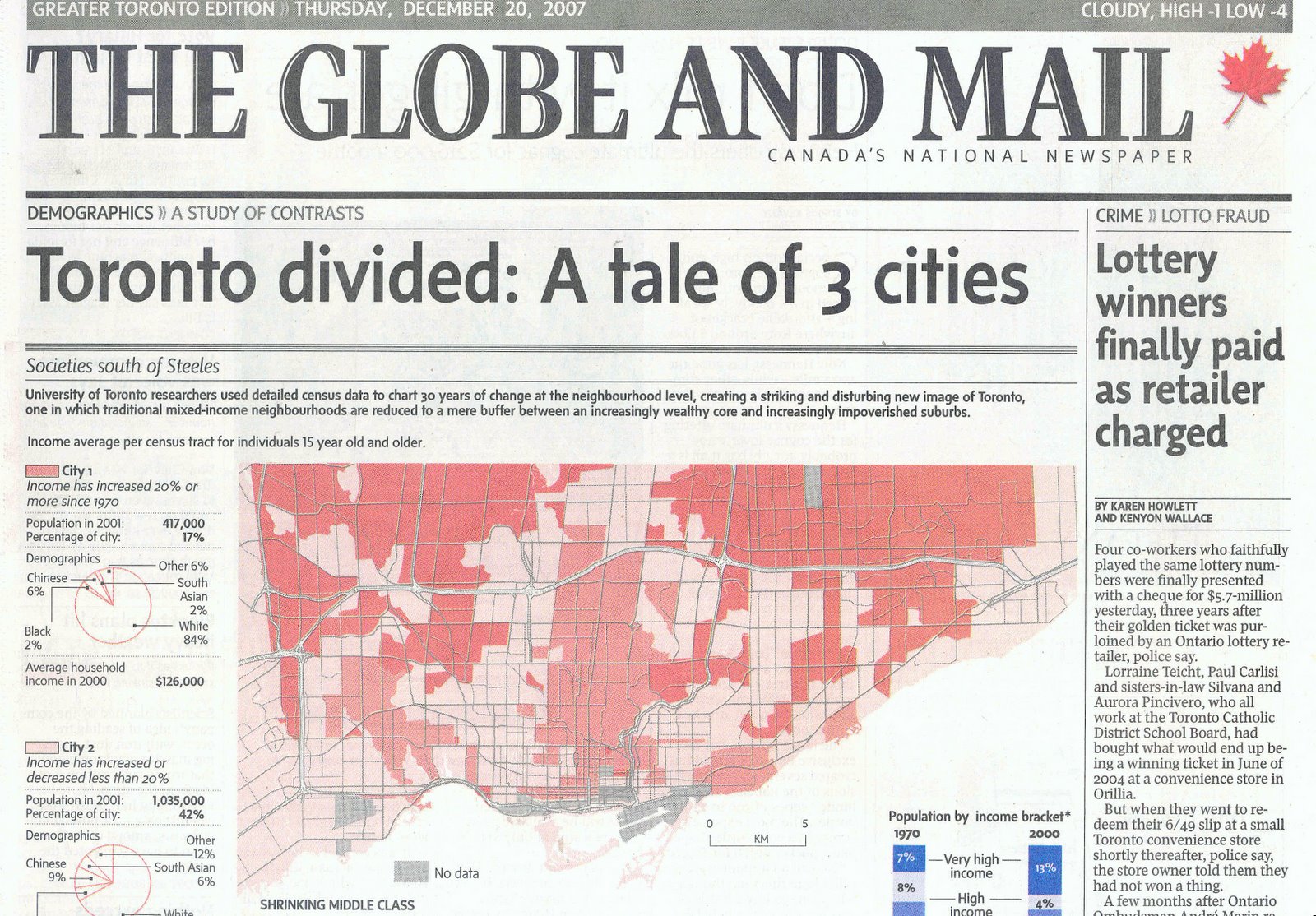

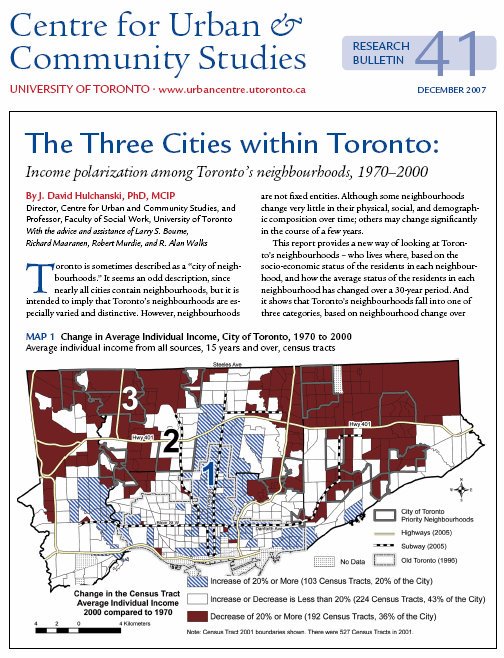

Three Cities: How Toronto has become such an economically divided city; Housing advice for the next mayor & council

"Well, it is better to know this than not to know it." This was one of Mayor David Miller's observations a couple of years ago when he saw an early draft of the research into Toronto's "Three Cities."

"Well, it is better to know this than not to know it." This was one of Mayor David Miller's observations a couple of years ago when he saw an early draft of the research into Toronto's "Three Cities." This initiative highlights the fact that just over one million people, or about 43% of the city's population, live in what we call "City #3" – the once middle-income, mainly car-oriented and under serviced neighbourhoods of

18 September 2010

The invention of homelessness

11 September 2010

Report documents the extent of housing subsidy discrimination between homeowners ($15.8 billion annually), private renters ($1.3 billion), and social housing ($2 billion); Most of Canada’s housing-related subsidies do not assist those in need

A report, Government Subsidies to Homeowners versus Renters in Ontario and Canada, by housing economist Frank Clayton, estimates the size of the imbalance in the way that owners and renters are treated by Canada’s various housing subsidy programs. Housing-related subsidies include both direct budgetary expenditures and tax benefits (commonly referred to as tax expenditures).

When any household seeks a place to live there are two basic starting decisions: to own (buy a house or condo), or rent. Canada’s small social housing sector, about 5% of all housing, means that 95% of Canadian households must seek housing in the private sector – either buy a house or condo, or rent from the private rental sector.

A housing system ought to be neutral in terms of subsidies provided to owners and renters. Why should one form of housing tenure

09 September 2010

In homelessness, diversity does not mean complexity; Another ten chapters added to Finding Home eBook

25 August 2010

Affordable Housing: Global Trends -- a presentation by Christine Whitehead

For a very clear and helpful review of the notion of “housing affordability” see the PowerPoint presentation by Christine Whitehead (professor of economics, LSE & Cambridge) – from a keynote address at a recent housing conference of the Asia Pacific Network for Housing Research.

20 August 2010

TRANSIT CITY: More Broken Promises – McGuinty Fails Toronto Transit this Time

Mayor Miller is correct when he refers to the Ontario government’s recent budget decision to postpone $4 billion in GTA transit expansion as “disgraceful,” “thoughtless” and “beyond short-sighted,” a decision that makes “absolutely no economic sense” and “it makes no sense from a social policy perspective.”

This most recent broken promise, however, should not be a surprise.

The Ontario Liberal party, ever since the inexperienced dark horse candidate for leader surprised even himself in not only winning his

10 July 2010

UofT EDGE Magazine: Goodbye, middle-income neighbourhoods -- Profile of the Neighbourhood Change Community University Research Alliance

25 April 2010

New Research Grant Awarded: Neighbourhood Trends in the Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver City-Regions, 1971 to 2006

21 December 2008

Housing as a Financial Weapon of Mass Destruction: Homeownership ideology & self-interest trump responsible housing for low-income households

The prosperity of a few years ago, such as it was — profits were terrific, wages not so much — depended on a huge bubble in housing...” -- Paul Krugman, NY Times, Dec. 22, 2008

'What an ideology is, is a conceptual framework with the way people deal with reality... Everyone has one. You have to - to exist, you need an ideology. The question is whether it is accurate or not."-- Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, from 1987 to 2006, at the Congressional House oversight and government reform committee on 23 October 2008

20 November 2008

Toronto: Poor city beside rich city

10 November 2008

Toronto’s Persistent Neighbourhood Polarization Trend: One-third of neighbourhoods on a 25-year income spiral, 9% going up, 25% going down

by David Hulchanski and Richard Maaranen, Cities Centre, University of Toronto, November 2008

Nine percent of Toronto’s census tracts have been increasing in average individual income. These 46 areas are joining or have joined the ranks of the city’s higher income areas. Most are also located adjacent to Toronto’s already higher income neighbourhoods – a further clustering and consolidation of a demographic that is not only financially well of, but also mainly white with a relatively small share of Toronto’s celebrated ethnocultural diversity.

Many more neighbourhoods, however, 128 census tracts (25% of the city), have been consistently declining in average individual income for the two and half decades. These formerly poor and middle-income areas are now much poorer. Most are in the car-oriented inner suburbs built in the 1950s to the 1970s. These areas are mainly and increasingly non-white with a disproportionate share of newcomers.

Still in the middle.

Two-thirds of the city’s neighbourhoods (341 census tracts) do not have a persistent direction of change but many are still better off or worse off now compared to 25 years ago. Of these, 88 are 10% or more better off in 2005 than 1980 (17% of the City) and 130 are 10% or more worse off over the same period (25% of the City). Relative stability, that is, income is neither 10% higher or lower in 2005 than 1980, only occurred in the remaining 123 census tracts (24% of the City).

The map shows only persistent change among Toronto’s census tracts over the past 25 years. It is not a map of rich and poor areas. It is a map of change.

What is significant, in addition to the fact that fully one-third of the city has a consistent upward or downward income trajectory over such a long period, is that there is a high degree of geographic concentration within the trend. The pattern is not random. Wealthy and poor areas are consolidating. Those who have choice – enough money to choose their neighbourhood, are abandoning parts of the city.

Note on Method

How was the change calculated? The map is based on an analysis of census average individual income for five census years (1981, 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006).

Individual income is the census category for income of persons 15 and over from all sources. It has an advantage over household income for determining the socio-economic status of people living in an area as it controls for differences in household size. The number of persons in each household with income is increasingly uneven across the City with a large divide between the downtown area and the suburbs. Median income is not used here because it has the disadvantage of hiding the extent of the high and low incomes, since most neighbourhoods have at least a few high or low-income people. Use of any of the income categories in the census, however, produces similar results. This is discussed further in: J.D. Hulchanski, The Three Cities Within Toronto: Income polarization, 1970–2000, CUCS Research Bulletin #41, December 2007.

01 October 2008

from ... The New Yorker: When owning isn’t better: What was a savings plan is now pushing some into indentured servitude

By James Surowiecki The New Yorker, March. 3, 2008

----------------------

In March 2008, about half a year before the global economic crisis broke, caused in part by the US housing bubble and all the bad mortgage lending practices, The New Yorker published the following brief note.

It correctly pointed out that owing a house is a risky way to have a savings plan and that long term mortgages were a form of indentured servitude. It failed, as we all did, to see how thoroughly the housing market could wipe out the savings of so many millions of lower income American homeowners. --jdh

-------------------

Americans may disagree about nearly everything, but few contest the idea that owning your home is a good thing. Paeans to homeownership are a commonplace for American politicians, and, since the nineteen-thirties, public policy has been designed to make home buying cheaper and easier. Homeownership, the argument goes, has tremendous social benefits, stabilizing neighborhoods and making people more willing to invest in their communities. And it has economic benefits, too, serving as a forced-savings program that allows people to leverage their incomes and build wealth. Homeownership “provides financial security for families,” Mel Martinez, the former H.U.D. Secretary, has said, and it “generates economic strength that fuels the entire na

tion.”

That never seemed more true than in the years from 1994 to 2005, when the percentage of Americans who own homes rose by almost ten per cent, and the amount of wealth tied up in property soared. But our veneration of homeowning has blinded us to the fact that, along with the benefits, it has some very real costs — costs that only get bigger as the ranks of homeowners swell. The housing boom undoubtedly helped the economy’s growth rate and made lots of first-time home buyers happy. Unfortunately, it may also end up prolonging and deepening the current downturn.

In part, this is due to the nature of the boom, which was stoked by cheap credit and lax lending standards. Buying a home used to require a sizable down payment: in 1976, the average for a first-time buyer was eighteen per cent. By contrast, a National Association of Realtors study of first-time buyers between mid-2005 and mid-2006 found that almost half put down nothing at all, and that the median down payment was just two per cent. If you earn eighty thousand a year, no one will lend you four hundred thousand dollars to buy stocks, but plenty of people were willing to lend you that money to buy a house. As long as home prices were rising, all this leverage seemed like a good thing: it let people buy homes that they couldn’t otherwise afford, and maximized their return on investment. But, with home prices sinking — in the final quarter of 2007, they were down almost 9 percent from the year before—the downside has become clear: as many as fifteen million homeowners now owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. Homeownership isn’t building wealth for these people; it’s locking them into indentured servitude.

The problem was exacerbated by an explosion in home-equity loans, fuelled by our faith that house prices can only rise. According to a recent study by the Federal Reserve, homeowners took out more than six hundred billion dollars in home-equity loans between 2004 and 2005 alone — ten times as much as they had a decade earlier — and are spending much of it on personal consumption. That destroys the forced-savings aspect of homeownership, since people are using up their home equity instead of saving it for the future. And it means that many homeowners have to devote more and more of their income to paying off home-equity debt, contributing to the current slowdown.

Even without lending and borrowing excesses, though, our high rate of homeownership would likely create problems as the economy slows. To recover from recession, economies need prices to fall until they reflect genuine supply and demand. With certain kinds of assets, like stocks, these adjustments take place quickly, sometimes viciously so. Buying and selling houses, though, is a far slower process. The good thing about this is that housing prices never suffer crashes on the scale that you sometimes see in the stock market. The bad thing is that it can take a long time for housing prices to reflect reality. Homeowners, as economists have shown, tend to remain unreasonably optimistic about the value of their homes, and they hate to drop their asking price. As a result, existing-home sales in the U.S. are now at a nine-year low.

Home ownership also impedes the economy’s readjustment by tying people down. From a social point of view, it’s beneficial that homeownership encourages commitment to a given town or city. But, from an economic point of view, it’s good for people to be able to leave places where there’s less work and move to places where there’s more. Homeowners are much less likely to move than renters, especially during a downturn, when they aren’t willing (or can’t afford) to sell at market prices. As a result, they often stay in towns even after the jobs leave. That may be why a study of several major developed economies between 1960 and 1996, by the British economist Andrew Oswald, found a strong relationship between increases in homeownership and increases in the unemployment rate; 10 percent increase in homeownership correlated with a two-per-cent increase in unemployment. (In the U.S., it may be worth noting, the states that have the highest unemployment rates — states like Alabama, Michigan, Mississippi — are also among those with the highest home ownership rates.) And reluctance to move not only keeps unemployment high in struggling areas but makes it hard for businesses elsewhere to attract the workers they need to grow.

This doesn’t mean that the U.S. should become a nation of renters—even if both New York City and Switzerland show that high rates of renting are compatible with great prosperity. With the bursting of the housing bubble, though, it’s time not just to scrutinize the excesses of our home-buying process but to recognize the risks and costs inherent in owning a home. Sometimes the price—for the home buyer and for the economy as a whole—is too high to pay.

15 July 2008

Australia’s Housing Affordability Crisis -- Similar to Canada's: What to do about it?

"Although affordability problems for purchasers tend to receive most media attention, the largest group of households experiencing affordability problems are not purchasers but are households in the private rental market. For many of these households, home ownership is not something they can even aspire to." p.201

"While 16 per cent of all households had high housing cost ratios in 2002–03, more than 28 per cent of lower income households were in housing stress.For lower income private renters, however, the incidence of stress was 65 per cent. For lower income purchasers it was 49 per cent." p.207

"This suggests that the most effective long run solutions to housing affordability problems lie in addressing the underlying determinants of demand and supply. With continued pressures from increased population growth and real per household incomes, demand is likely to be reduced only by reducing the attractiveness of housing as an investment asset. Demand side subsidies, such as the untargeted first home owners grant to first homebuyers are unlikely to be effective.

"The second key observation is that the media tendency to define affordability problems by high or increasing housing cost ratios for purchasers is largely misplaced. Most home purchasers have relatively high incomes and are not forced into the undesirable trade-offs that lower income households face when their housing costs increase. There are significantly more renters than purchasers in housing stress and the incidence of housing stress is significantly greater among private renters. Many of these households face the prospect of never being able to gain access to the economic an social advantages provided by home ownership.

"This suggests that a change is needed in the direction of Australia’s housing policies away from those that focus on home ownership and towards those that increase the supply of well located affordable rental housing to meet the needs of those on lower incomes who are likely to be long-term renters. A strategic rental housing policy framework is essential to foster adequate and stable levels of investment in rental housing."

24 May 2008

The Ghettoization of "Toronto the Good"?

The "elephant in the room" during discussions of most any socio-economic and demographic trend relating to Toronto is the growing geographic, ethnocultural, and skin colour (white, non-white) polarization of the city.

Is Toronto creating its own version of ghettos? If so, they will not be American style ghettos. Those arose from U.S. specific historical circumstances and at a different time.

19 May 2008

What is "social mix"? Why are "inclusive" neighbourhoods desirable? Are they desirable?

On May 15, 2008 a public forum and a specialized seminar were held on the theme of “Social Mix” & Inclusive Communities, International Perspectives: A Discussion of Experience & Recent Research from Australia, England, France & Canada.

These events were organized by the five-year neighbourhood change community university partnership between St Christopher House and the University of Toronto’s Cities Centre (formerly Centre for Urban and Community Studies). See: www.NeighbourhoodChange.ca

A research team (described below) happened to be meeting in Toronto. For the forum and seminar, they were joined by one of Australia’s leading researchers on social mix and public housing revitalization, Kathy Arthurson.

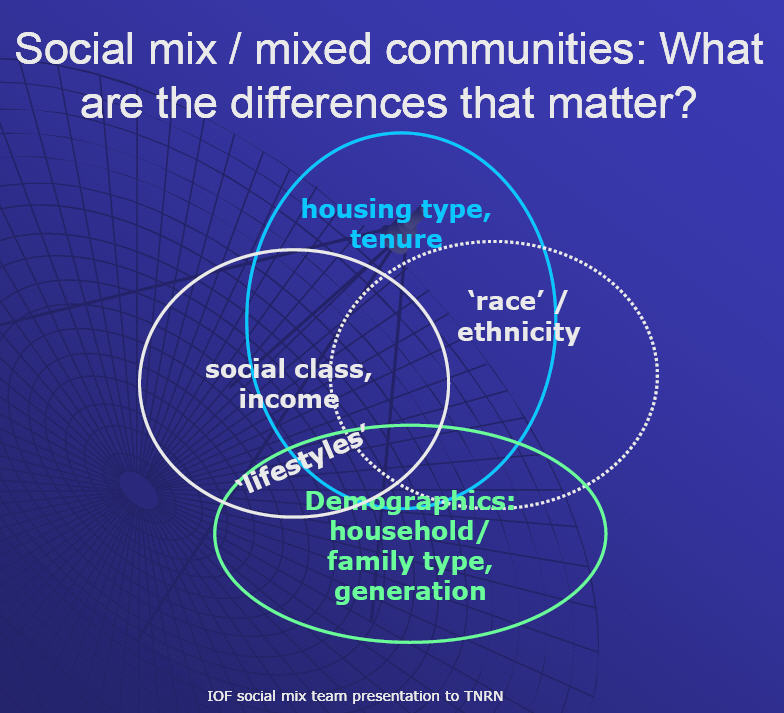

The following is taken from the presentation the visiting team made at a special seminar of the Toronto Neighbourhoods Research Network (see : www.TNRN.ca).

_______________________________

Project title

‘Social mix’ and neighbourhood revitalization: linking globalized policy perspectives to locally embedded experiences – towards a transatlantic comparison

Funding

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, International Opportunities Fund Research Grant (2006-2008)

Research team

Tom Slater and Gary Bridge, School of Policy Studies, Univ. of Bristol

Marie-Hélène Bacqué, Yankel Fijalkow and Lydie Launay, LOUEST, CNRS, Paris

Annick Germain, Amy Twigge and Damaris Rose, Centre Urbanisation Culture Société, INRS, Montréal

Project rationale

Since mid-1990s, marked resurgence in attention and apparent international convergence around value of ‘social mix’ / ’mixed communities’ as urban policy tool

- Why has this happened?

- Is there a shared vocabulary and similar rationale and goals?

- Are there differences in values and objectives between national contexts, and between local actors in a given context?

- Explore international circulation of ideas regarding the merits of ‘social mix’ / ’mixed communities’

- Explore links between national, sub-national and local scales of policy thinking

- Decode different local actors’ narratives of social mix in inner-city neighbourhoods undergoing ‘revitalization’: what does ‘mix’ mean? what is a ‘mix’ policy meant to achieve? how do ‘mixed neighbourhoods’ work out in practice?

The team is currently producing their findings.

_________________________________

Preliminary Conclusions

(1) The changing paradigm of social mix?

- Historically, 2 phases of advocacy for social mix:Phase 1 (c.1900): utopian vision of social class reconciliation through sharing of urban space

- Phase 2 (post-WW2 welfare state): egalitarian ideal of spatial justice

- Phase 3: a neoliberal tactic for shifting responsibility for aiding the poor onto non-state actors; e.g., funding affordable housing via private-sector dominated developments; poverty deconcentration to achieve social integration by ‘the community’ or via middle-class influence

- Implicit or emerging agenda: social mix = ethnic mix?

- Ethno-cultural cohabitation issues?

- The commodification of cosmopolitanism?

- This conceptualization opens up space for exploring competing discourses, in particular, the gap between romantic visions of social mix and the reality of negotiations ‘on the ground’

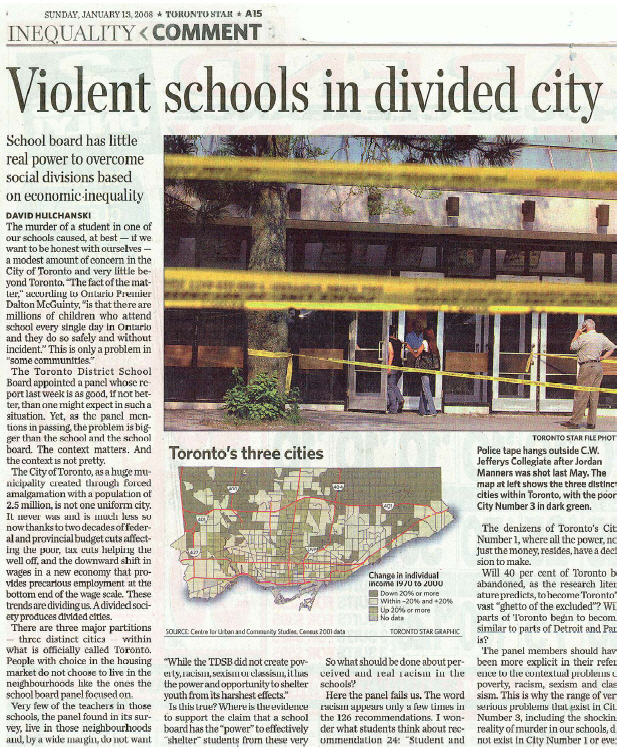

13 January 2008

Op-ed: Violent Schools in Divided City -- Toronto school board's report on school violence

the matter,” according to Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty, “is that there are millions of children who attend school every single day in Ontario and they do so safely and without incident.” This is only a problem in “some communities.”

the matter,” according to Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty, “is that there are millions of children who attend school every single day in Ontario and they do so safely and without incident.” This is only a problem in “some communities.”