"Well, it is better to know this than not to know it." This was one of Mayor David Miller's observations a couple of years ago when he saw an early draft of the research into Toronto's "Three Cities."

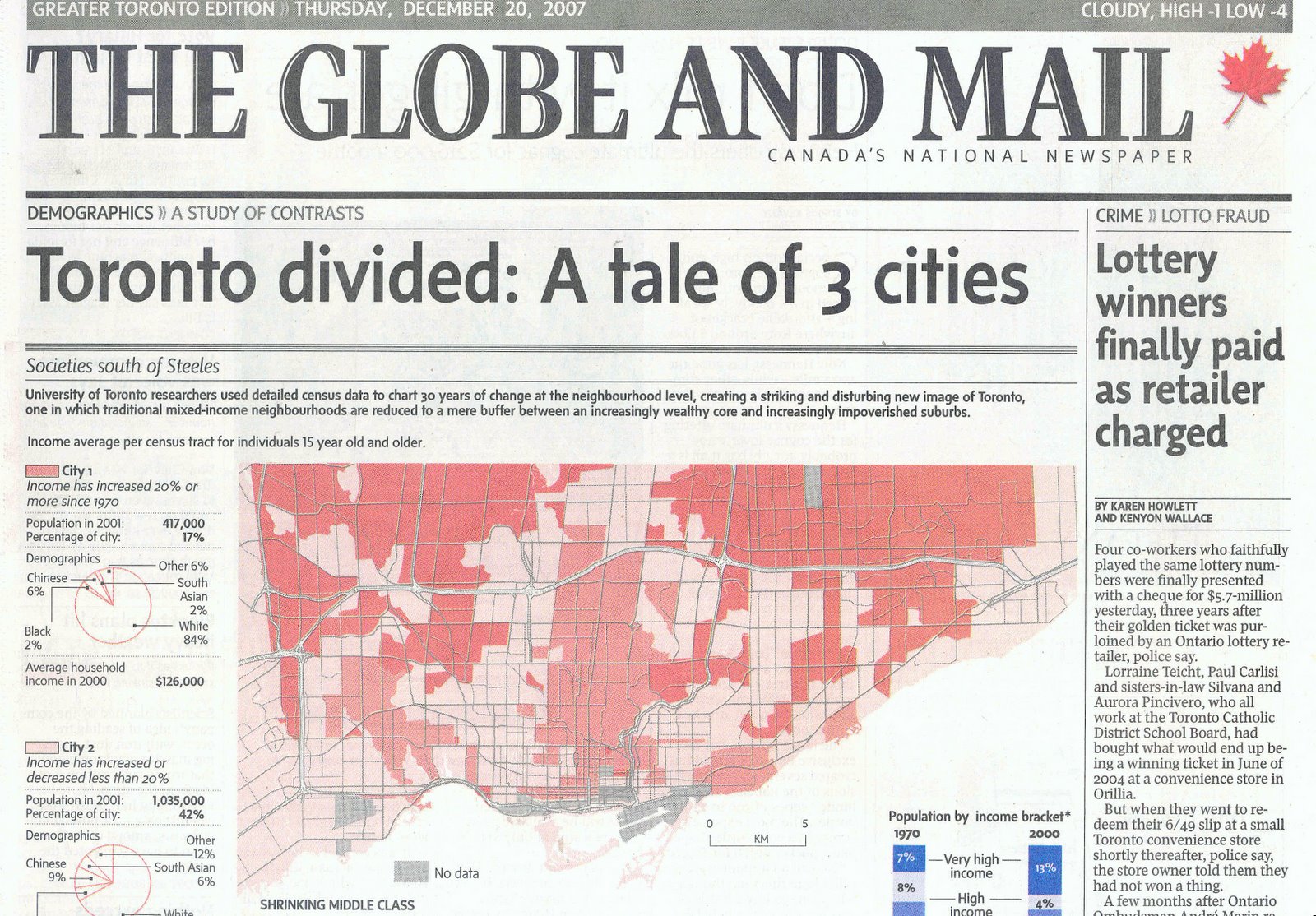

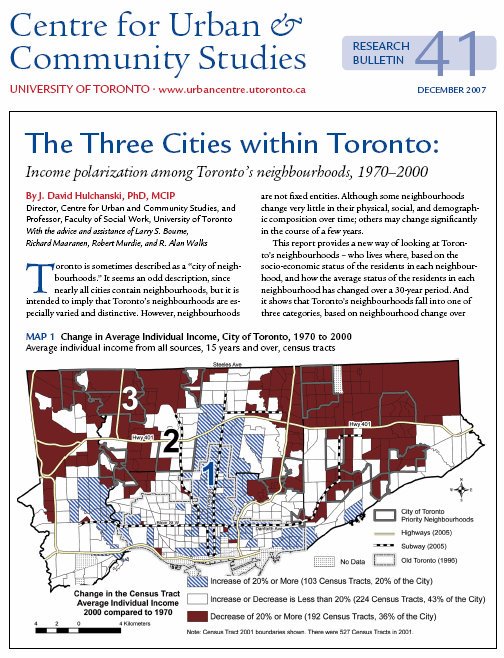

"Well, it is better to know this than not to know it." This was one of Mayor David Miller's observations a couple of years ago when he saw an early draft of the research into Toronto's "Three Cities." This initiative highlights the fact that just over one million people, or about 43% of the city's population, live in what we call "City #3" – the once middle-income, mainly car-oriented and under serviced neighbourhoods of northern Etobicoke, parts of North York, and most of Scarborough that were first built in the 1950s but have been declining in average income and socio-economic status since the early 1970s.

As many commentators point out, Toronto is ethnically and culturally diverse. But much of this diversity is in City #3, where the population is two thirds non-white – compared to City #1, the city's wealthiest and primarilycentral neighbourhoods, which is 82% white. Over the past quarter century there has been a doubling in the number and a substantial geographic consolidation of the City #1 neighbourhoods. At the same time, the in-between city, City #2 – once a vast middle-income majority of Toronto – isshrinking in size as its neighbourhoods either filter upward or, mainly, filter downward in average income.

A major outcome of this shift in the city's social and economic landscape is the problem of more people – especially those who have to rent – not being able to afford adequate housing appropriate to the size of their families. Many of the city's renters live in overcrowded conditions. Half of the renters in City #3 are spending 30% or more of their income on rent. And yet the federal and provincial governments have no ongoing commitment to supplying additional social housing units or rent supplements.

The City's social housing waiting list includes 138,000 people – that's greater than the populations of Guelph, Brantford. or Peterborough. The waiting list includes 29,000 children and 12,000 single parents. Many thousands of people are homeless every night, either as "visible" homeless on the street and in emergency shelters, or as "hidden" homeless and at serious risk of losing their homes.Over 4,000 people in Toronto use overnight shelter beds and related daytime services. There is money spent to help maintain people in their unhoused state; much less is spent on keeping people from becoming unhoused or quickly rehousing them. These are well-known housing problems. Not much is currently being done about them, which is bad enough. On top of this, looming large (and tall!), is a housing problem most Torontonians still know little if anything about.

The City's social housing waiting list includes 138,000 people – that's greater than the populations of Guelph, Brantford. or Peterborough. The waiting list includes 29,000 children and 12,000 single parents. Many thousands of people are homeless every night, either as "visible" homeless on the street and in emergency shelters, or as "hidden" homeless and at serious risk of losing their homes.Over 4,000 people in Toronto use overnight shelter beds and related daytime services. There is money spent to help maintain people in their unhoused state; much less is spent on keeping people from becoming unhoused or quickly rehousing them. These are well-known housing problems. Not much is currently being done about them, which is bad enough. On top of this, looming large (and tall!), is a housing problem most Torontonians still know little if anything about.

Toronto has more residential highrise buildings than any other city in North America, except for New York. Among these residential towers are 1,100 built between the late 1940s and early 1980s. They are mainly rental and house over 25% of the city's households: 280,000 units. Almost half of the city's rental housing stock is in these aging and often overcrowded buildings. Half of the households in City #3 live in high-rise apartments (compared to 30% in Cities #1 and #2).

With its limited funds, the City has established a small Tower Renewal program. It is the start of something that should be a major federally and provincially funded initiative. Most of the towers are in clusters, with unused land around them. A building rehab program with energy retrofits, including some additional development on the unused land, carried out as a grassroots community development initiative, with a job training component, all add up to community renewal – both physical and social.

With its limited funds, the City has established a small Tower Renewal program. It is the start of something that should be a major federally and provincially funded initiative. Most of the towers are in clusters, with unused land around them. A building rehab program with energy retrofits, including some additional development on the unused land, carried out as a grassroots community development initiative, with a job training component, all add up to community renewal – both physical and social.

Though it is indeed better to know than not know, there are growing housing- related social and economic trends that the new mayor and city council can only ignore at great peril. Toronto is a divided and increasingly polarized city, and there is nothing on the horizon to reverse this trend. The number of people facing housing quality and affordability problems is huge. It is a problem that is highly concentrated in neighbourhoods that urgently need investment and renewal.

The federal and provincial governments must be prodded by civic leadership into doing what they know they ought to be doing. All great cities need help with affordable housing, and there is no excuse for widespread homelessness. Mayor Miller initiated and promoted the Tower Renewal program. This is the key to addressing the growing divisions and the decline within the city. A ten-year major program would renew the aging rental stock, be a big economic stimulus, and produce many environmental benefits, remaking the post-war suburban landscapes into desirable places to live. Tower Renewal requires improved public transit in City #3. Of the TIC's subway stations, 60% are in City #1, and only 30% are in City #3 (mainly the Scarborough RI).

When the Premier announced that the Province would break its funding promise for implementation of the Transit City plan, it was not too surprising that it was the City #3 part of the plan was "postponed." Without improved transit it is difficult for those neighbourhoods to ever improve. Money buys choice. People with options stay away from poorly served neighbourhoods, leaving these landscapes for people who have little choice.

The segregation of the city by socioeconomic status and ethno-cultural origin need not continue. It is not inevitable. It can be slowed and reversed. The jurisdiction and financial capacity of the federal and provincial governments are sufficient to reverse the trend. A wealthy society can use its resources to make a difference. The City administration must make this task its focus – with its own limited resources and by seeking the necessary support from senior governments.

On day one, Toronto's new mayor will already have on hand an affordable housing plan (Housing Opportunities Toronto), the Tower Renewal initiative, the Transit City plan, and a priority neighbourhoods initiative in the inner suburbs (a joint effort with The United Way). These are key components of a complementary renewal strategy for the entire city with a focus on City #3. They are a nice legacy of the current mayor and council. These need to be implemented. They are not optional.