In the late 1970s I was a graduate student living in Alexandra Park Housing Co-operative near Queen and Bathurst. Wayne Roberts was also living there. He had just finished his PhD.

Wayne Roberts is a well-known and highly respected food policy and environmental activist who writes a weekly column for Now Magazine.

After not seeing each other for more than a decade we were twice almost connected this year via the media. First by CBC's Metro Morning. I was about to leave for the CBC studio one morning to be interviewed and there was Wayne on-air being interviewed. I was hoping to see him but he was long gone by the time I was in the studio.

Then, this week, in his NOW Magazine column, Wayne mentioned something he recalls me saying long ago, probably in the early 1980s. He mentioned that during the municipal election campaign this year

"city-oriented activists tend to emphasize issues of the city, and not issues in the city, to use a distinction I learned many years ago from a remark tossed off by housing expert David Hulchanski."

That helpful insight, that we need to distinguish between problems in cities from problems of cities, is not mine but my dissertation supervisor, Hans Blumenfeld.

Hans Blumenfeld, one of the leading figures in 20th-century urban and regional planning, wrote the following:

The key point here is that there are common problems faced by many Canadians, problems that have nothing to do with the City of Toronto's administration but with, as Blumenfeld notes, "the social, economic, and political structure of our society." With a population of 2.6 million, there is a concentration of people affected by macro-level economic and political policies and conditions."Poverty, unemployment, violent class and race conflicts, 'alienation,' and 'anomie' are certainly problems in the city , but they are not problems of the city. They are problems produced by the social, economic, and political structure of our society. They would exist whatever our pattern of settlement -- even if we, instead of congregating in metropolitan areas, all dispersed into small towns or hamlets. In fact, they do exist there. They are more visible where they are concentrated; this is all to the good, because recognition of a problem is the first step toward dealing with it." (Hans Blumenfeld, preface to the Canadian paperback edition of his The Modern Metropolis: Its Origins, Growth, Characteristics and Planning, Selected Essays (edited by P.D. Spreiregen, Harvest House, Montreal, 1971).

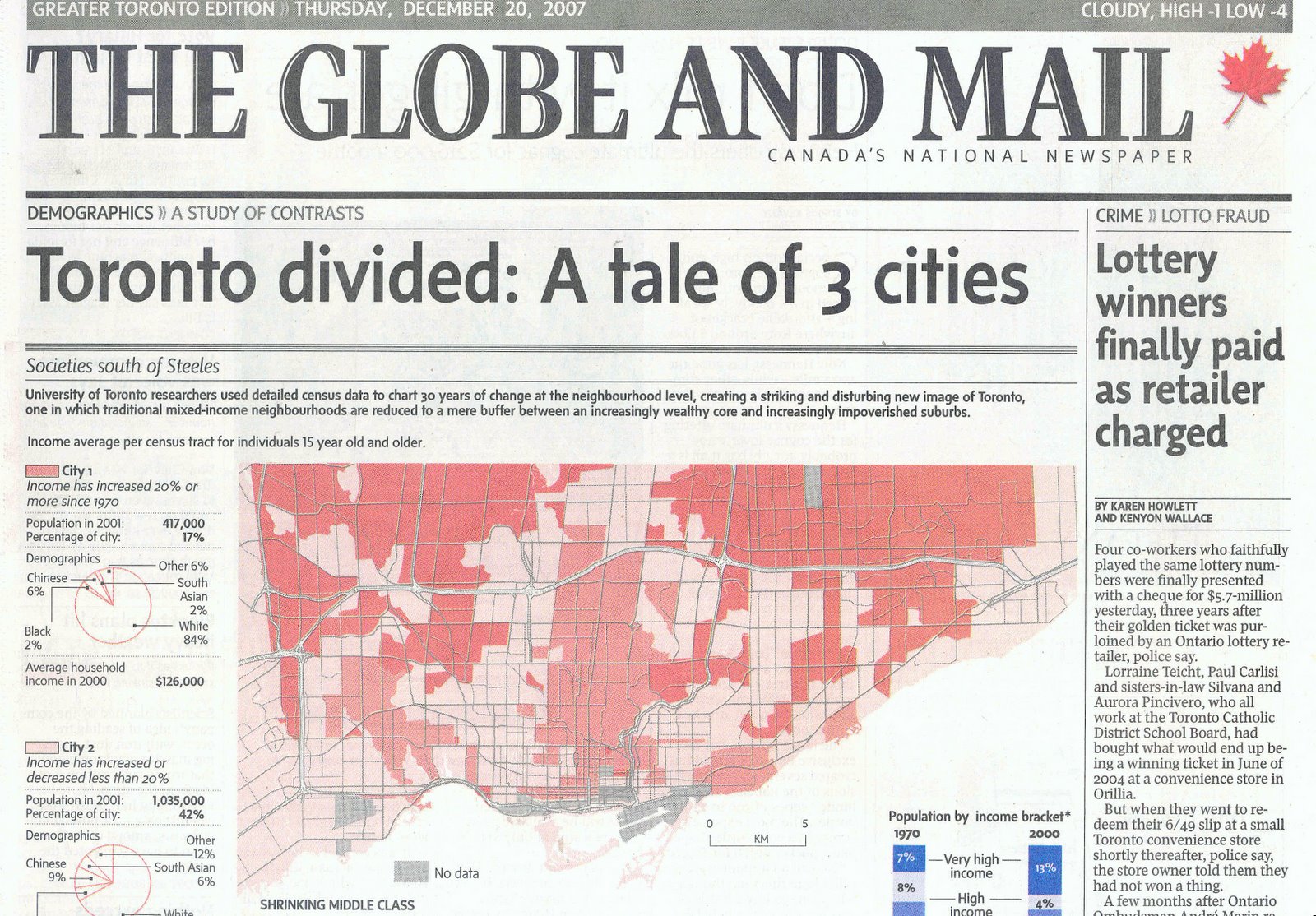

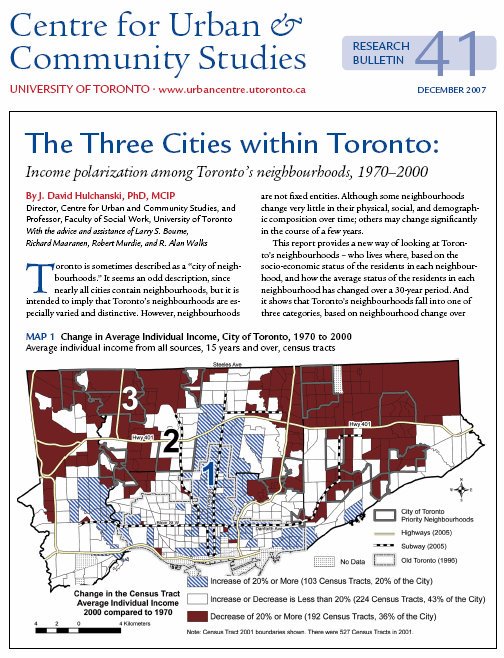

Thus the unexpected happened in Toronto's mayoral election. The sections of the city that are still middle income and the much more numerous sections that are increasingly low and very low income (referred to as City #2 and City #3 in my "three cities" analysis of Toronto), voted together for Rob Ford.

The portion of the city that is wealthy and high income, as well as, in places, socially mixed, with a range of incomes (City #1), voted for other candidates, most of whom had detailed platforms about municipal issues -- the problems of Toronto.

This election, in large part, was likely not about municipal issues (problems of the city) but a reaction to how hard life has become living in an expensive city where all the obvious public and private sector investment, including use of municipal resources, is taking place in City #1. Yet municipal taxes and special fees keep going up.

Rob Ford was an almost accidental candidate for mayor. Most in the media and among the elite chattering class initially thought he was an odd-ball fringe candidate -- until the first major independent poll was released. He had no real platform other than to cut wasteful spending and save taxpayer money. He talked about traffic congestion -- a terrible problem particularly in the inner suburbs where transit service is poor and distances great. The more frequent rapid transit services (subways and streetcars) are mainly in City #1.

If polled, most voters could likely repeat the two main themes, and the only topics, Ford talked about during the campaign: stopping the waste and getting spending under control; and eliminating unnecessary taxes. This would, if feasible, help out folks being squeezed by the high cost of living in Toronto.

Given the conditions of our times, all the societal problems that manifest themselves in concentrated form in Toronto, Ford just sat back as so many of the alienated, the disenfranchised, and the angry, together with traditional hard line conservatives that form his base, parked their votes with him. He quickly became the populist candidate.

As Wayne Roberts concludes in his column, the issues of cities indeed require urgent political attention, but so do the issues in cities relating to overall social and economic well-being. Though these are the staples of federal and provincial politics they cannot be ignored at the local level -- the level at which they are "lived."

The Rod Ford administration is going to have four difficult years. Toronto has many problems, few of which he addressed during the campaign. His simple slogans that focused on the anger and resentment of voters will have little impact on societal problems -- the problems in the city that likely explain his electoral success this year.

Traffic will continue to get worse each of his four years in office; transit will not become much better (especially in City #2 and City #3 where the Premier has decided to postpone transit improvements); and any severe cuts in core city services will mainly hurt the part of the city that voted for him, where services are, for the most part, not very good to begin with.

------------------------------------------

News

The dish on what’s eating populists

By Wayne Roberts

Now Magazine, Toronto

Strange to think it, but the parallels between last week’s local election and the U.S. midterms are too close for comfort.

The core issue in both, to my mind, is the fact that governments have moved anti-recession intervention right off the table, turning the vulnerable in the population into easy pickings for right-wing populism.

In general, progressives are spending less time pushing public realm solutions because many have lost heart, much like Tea Partyites, that governments will or can deliver.

In Toronto, for example, city-oriented activists tend to emphasize issues of the city, and not issues in the city, to use a distinction I learned many years ago from a remark tossed off by housing expert David Hulchanski.

Poverty, hunger, unemployment and housing problems exist everywhere – the countryside, exurbs, suburbs and city alike. But problems of the city – traffic congestion, overcrowding, public transit, garbage – live in a non-parallel universe.

Think of the airtime given to things like bike lanes or TTC issues and the flared-up resentment generated by them.

Compare that to the political attention paid to problems in the city like runaway housing costs, high rents, joblessness and food insecurity.

Social movements are in danger of losing sight of the in/of balance. That throws the entire political spectrum off-kilter and allows ultra-conservatives to lay claim to allegations that public money on the local level is being misspent. This is especially true in the burbs, where residents face more in the city problems.

City money, in fact, only goes to less economically driven programs like swimming pools, the arts and equity strategies.

It’s the feds and province that administer EI and job creation, and they’re doing it badly.

As well, as is true in both our city and the U.S., many people who have progressive views on social and economic issues have conservative views on cultural and lifestyle questions – a paradox neo-conservatives are adept at exploiting.

People who feel their freedoms are being curtailed while their socioeconomic needs are ignored and their culture and lifestyle dissed often become “angry white men” of both genders. Hello, Tea Party.

If politics veer too far toward cultural and lifestyle issues wrongly branded “left,” “elitist” or both (as in the case of despised “latte liberals”), particularly in hard times, the populist right has a field day.

People who feel economically forgotten are going to get triggered by all kinds of surprising issues and be sensitive to all kinds of disparities. Expect anger when it takes longer on a computer or touch-?phone to fill out a government application for a service than for a developer to gain approval for another condo that excludes families with moderate incomes.

With Fox-like cunning, this political turmoil has been subject to manipulation because of the general distortion of government agendas since the 1990s on both sides of the border.

Corporations have been all but deregulated. A foreign corporation bought one-?time steel giant Stelco in Hamilton, for example, and recently shut it down without a murmur. Foreign owners are at the point of buying up Canada’s potash reserves, crucial for soil fertility, without a peep. In such ways, governments give large corporations almost total licence.

Instead of recognizing government as an equalizing force that can stand up to big corporations, many experience government as an intrusively regulating but not protective force. All the forms and procedures that have to be filled out and followed for simple matters, often by people with limited computer knowledge, are enough to make anyone join a Tea Party rebellion against thoughtless bureaucrats.

Food multinationals do what they please when promoting junk, yet someone who wants to sell fruit and veggies or healthy snacks off a cart on the street gets the third degree in our own city. At some point, someone will scream like Elvis, “Don’t you step on my blue suede shoes.” (In other words, “Don’t overtax my car.”)

Regulation has come undone in its disproportion. What seem like personal and private behaviours of ordinary people are regulated, e.g. smoking, while corporate giants are allowed to pollute communities, often with government subsidies and tax breaks.

If progressives are not livid about this unravelling of proportion, they shouldn’t be surprised when some on their right steal their thunder and get away with presenting themselves as populists instead of elitists. The of issues of cities require urgent political attention, but so do the in issues of social and economic well-being – jobs, housing and food access being the most obvious, and once the staples of politics.

That, I believe, is the cautionary tale of our local election and the U.S. midterms as well.

news@nowtoronto.com